The Road to Jerusalem

A personal meditation on Israel and Jewishness, with an angry tirade thrown in for good measure

Dear reader: I wrote the essay below for a writing class I had to take to fulfill a requirement for my BA, which I will finally earn this summer after twenty years of slow and unsteady progress. As I’ve received some positive feedback for it (the essay, not the slow progress), I decided to share it here for a slightly wider audience. Please share it with anyone who might be interested.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, I was in the nurse’s office, where I liked to pass the break between prayers and first period—if I didn’t skip the morning prayer service altogether—chatting with the nurse. A news report interrupted the music on the oldies station that always played softly in the room: A plane had hit the north tower of the World Trade Center.

“Terrorism!” the nurse gasped.

My first instinct was skepticism: Pfft. Terrorism? Come on. I said, or maybe just thought, that we shouldn’t jump to conclusions. It might’ve been an accident!

I was fifteen.

I don’t remember much else about that day. We all sat in classrooms watching the news unfolding on TV while arrangements were made to get us home. A year later, amid the DC sniper attacks, we were sent home again after a shooting just a few minutes’ drive from the school. I joked that we’d been having more terrorism days than snow days of late.

Meanwhile, the Second Intifada was a constant parallel reality blowing up the lives of our fellow Jews, including relatives and friends. People were being killed in bus bombings, restaurant bombings, mall, hotel, and train station bombings, shootings, stabbings, and, in the case of one boy from our community and his friend, a stoning. Their blood was smeared on the walls of the cave where they’d been tied up and pummeled with rocks.

Every day, we recited extra psalms asking for God’s protection.

I raise my eyes to the mountains, from where will my help come?

The land of Israel is central to Judaism. More than that—it is the sine qua non. Judaism without Israel is like Christianity without Christ, Islam without Mecca, the United States without the Constitution. This is a crucial reason most Jews support the existence of the modern State of Israel, whose boundaries roughly correspond to the land inhabited by our distant ancestors. The word “Israel” appears about 2,500 times in the Hebrew Bible. “Jerusalem” and “Zion” have hundreds of mentions as well. References to the land of Israel throughout thousands of years’ worth of post-Biblical writing—law, exegesis, poetry, literature, prayer—are as innumerable as the dust of the earth and the stars of the heavens.

I visited Israel for the first time in 1998, at age twelve, with my father and two older brothers. We spent the bulk of the time in Haifa, where my grandparents lived. I had met them a couple times when they’d come to Maryland, but they were little more than strangers to me. It was difficult to feel close to them when they were so far away; the difficulty was exacerbated by their respectable but limited English and my own rather pitiful Hebrew. My father did not speak his native language with us growing up, and Hebrew pedagogy in Jewish day schools leaves much to be desired.

I visited Israel the second time on a high school trip in 2003. I was old enough this time to have a keener sense of my own alienness, of the gulf between myself and the strangers of this strange land. A number of my classmates, including Hillel, my closest friend, also had one Israeli parent, but they had grown up speaking Hebrew and visiting Israel regularly. It would not have been a stretch for them the call themselves Israeli. I vaguely recall self-identifying as “half-Israeli.” This was a delusion.

Most graduates from my school take a gap year in Israel before college. The majority spend that time studying in a yeshiva. I’d already chosen not to be observant and had no interest in spending a year studying Gemara, a pursuit that had up to that point mostly bored me to tears (or, more often, to sleep). My mother eagerly, perhaps desperately, informed me of the numerous other gap year opportunities available. I could travel, work on a kibbutz, study other things . . . But I said no. I didn’t want to. Instead, I started college, smoked too much weed, was depressed, dropped or failed my classes, and started working a dead-end job.

I wonder if my life would have been different—meaningfully, significantly different—if I’d spent a year in Israel, if my Gemara teachers had been more engaging, if my father had spoken Hebrew with me. Maybe I’d be a rabbi! Probably not, but who knows? Maybe I’d be a professor of Jewish history, like my brother. Maybe I’d have joined the IDF at eighteen and been killed at twenty in the Second Lebanon War.

Endless possibilities!

I went to Israel the third time with my father in the spring of 2007. I hadn’t seen my grandmother since the first visit in ’98. I never saw my grandfather again; he had died a year after that trip, when I was in eighth grade.

We had lunch one day with my grandmother’s brother Yanku and his wife Etti. My Hebrew at this time was at about the same level as it had been when I’d graduated high school—feeble—and I didn’t say much during the meal. After a while, Etti asked me how my Hebrew was.

“kacha kacha,” I answered. So-so.

“Kaka kaka,” Yanku quipped.

Etti launched into a passionate speech about how important it was for me to speak good Hebrew, as though my inability to do so were a personal failing, or a misguided choice she could talk me out of. “It’s your language!” she said.

“Ani maksim!” I assured her. I agree!

Except . . . no. What I’d actually just said was, “I’m delightful!”

“Maskim,” I meekly corrected.

Ugh. Kaka kaka was right.

Maybe it was a personal failing. I determined after this to make a serious effort to strengthen my Hebrew. I bought a dictionary and a book of verb conjugations, and studied both religiously. I insisted on speaking to my father in Hebrew, even going so far as to fake an Israeli accent as best I could. Six months later, when I returned to Israel for the fourth time, I was ready to put it to the test.

I did more on that trip than practice Hebrew. Never one for half-measures, I decided to make aliyah.

Later, when people there asked me why, I’d just shrug and say, “Felt like it.”

There wasn’t much more to it than that. I had just started taking classes again, one at a time, after a hiatus of a couple years. I was a fourth-year freshman working full time at a job I didn’t like. Hillel, with whom I was staying in the squalid basement apartment he shared with three roommates and a giant rat they named Feivel who came and went as he pleased through a hole in the wall, asked why I didn’t just make aliyah. Hillel had not done a gap year in Israel—he had gone after high school and never come back, apart from the occasional visit.

“Are you kidding?” I said. “That’s crazy, I can’t make aliyah.”

But I was unmoored and rudderless, and by the time I got on the plane home, I’d made an appointment with the DC area representative of the Jewish Agency to discuss the process of moving to Israel. Six months later, I was flying east again on a one-way ticket.

For my first five months in Israel, I lived in an absorption center1 called Ulpan Etzion. The residents lived together, ate together, studied Hebrew together in the onsite ulpan,2 and did everything (yes, everything) else together too. We came from all over the globe: England, Scotland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, Italy, Hungary, Venezuela, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand . . . I had a roommate from Russia who knew English, and another from Turkey who didn’t, but was happy to teach me Turkish profanity. I took a few guitar lessons with a Frenchman I spoke Hebrew with, though mostly he spoke it at me. My closest friend was Salome, an Indian Jew who had come to Israel to study choir conducting at the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance.

When I arrived on the first day of the session, the woman checking me in asked if I observed Shabbat or not. She was trying to room observant Jews together to avoid any awkward lifestyle clashes. The answer to her question was no. I liked to call myself “non-practicing Orthodox,” because it wasn’t as though I’d switched to some other denomination . . . I’d just stopped following the rules of the one I was in.

But I hesitated.

“Um . . .”

She was polite, but needed an answer.

“Not observant, I guess.”

They did not entirely manage to keep the observant separate, which did in fact result in at least one awkward situation. One night about three months in, I was hanging out with Salome, a couple of her music classmates, and a few of our ulpan friends. One of the latter, Elizabeth, a Canadian in her late twenties, told us she had arrived home late the previous Friday night and found her Orthodox roommate Inna sleeping in the hall. Elizabeth had left the light in their room on, and since Inna couldn’t turn it off, she dragged her mattress out to the unlit hallway.

“Wait,” interjected Nir, one of the music students. “I know you can’t turn a light on, but you also can’t turn if off?” He laughed. “That’s stupid.”

Non-practicing or no, I was irritated. Offended, even. Go back a few generations, and your ancestors were obeying the same rules as mine, or were at least aware of them. If you aren’t—fine, whatever. But who do you think you are, laughing, ridiculing the rest of us—them, I mean? The ones who keep our traditions alive? The ones who are doing it right?

In the fall of 2008, I worked for a few weeks on an archaeological dig in downtown Jerusalem. They even gave us T-shirts that read “archaeology worker” on them in Hebrew. We were excavating a site from the time of the Mamluks, a conglomeration of Turkic and Caucasian peoples whose ethnogenesis was their common enslavement by the Arabs as forced soldiers. They, or their freed descendants, ruled an area that included modern day Israel from the mid-1200s till the Ottomans took over in 1517.

The site in question was an ancient cemetery. We were digging up Mamluk skeletons and putting them in cardboard boxes, to be reinterred somewhere else, I guess. The centuries-old bones were brittle and spongy, and broke frequently. Every now and again someone would bash a skull in by mistake.

One day I was working on a grave with a girl named Hadar or Tamar or something like that. She asked me why American Jews keep making aliyah. I shrugged. “Zionism?” I suggested.

She emitted a sound between a grunt and a chuckle. “Is there such a thing?”

I don’t remember how I responded, but I imagine I was puzzled. Or maybe I figured her attitude was a pose, the kind of facile cynicism of the kid who goes off to college and discovers that everything she learned growing up was a lie. Now she’s one of a select, enlightened few who truly know what’s what, unlike this poor American rube sitting cross-legged in the dirt, digging up the seven-hundred-year-old bones of some Kipchak or Circassian and earnestly suggesting that diaspora Jews still hadn’t lost their hope, the hope of two-thousand years.

Around this time, I met an American doctor in an urgent care clinic who encouraged me not to take the cynical remarks of the Hadar-or-Tamars of the world to heart. A colleague of hers had just directed such a remark at me. Something along the lines of—What are you doing here? Why would you choose to leave America to live here? People immigrate to the US from literally every country on the planet, Israel included, and you come here? Are you stupid?

He must have been secular. A religious Israeli would get it, I think. Many seculars would too, for that matter. True, I moved to Israel because I had nothing better to do. But I could more easily have moved to Hollywood to try and make it big, or lost myself in the great north woods in order to truly find myself, or gone to New York City to do whatever it is people do in New York City. There was no shortage of American clichés available to me if I wanted to drop everything—what little I had to drop—and start anew somewhere.

I remember saying “Felt like it” one time with my accustomed shrug, and the girl I said it to was so delighted that she ran over to a friend, brought her back, and asked me to say it again. They didn’t need me to explain. They got it.

Maybe, I thought, I was one of them.

One Shabbat in 2009 or ’10, my friend Lior and I went for a walk. There isn’t much else to do in Jerusalem on a Saturday. Unlike modern, secular Tel Aviv, the capital shuts down from sundown on Friday to sundown on Saturday. Almost every store and restaurant is closed. The streets are mostly empty of cars, and certain neighborhoods are blocked off altogether to vehicular traffic.

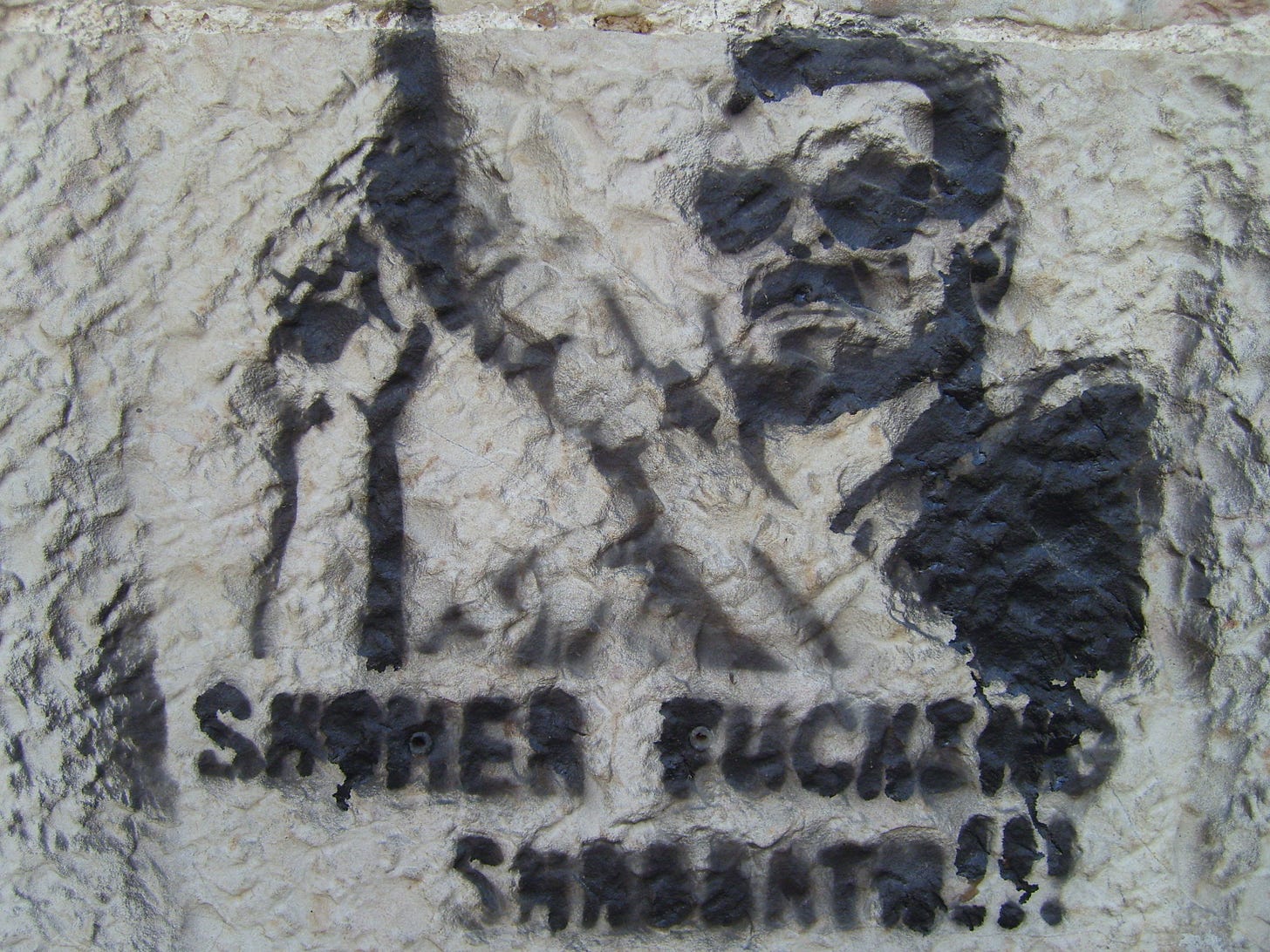

We walked to Nachlaot, a charming labyrinth of a neighborhood comprised of winding alleyways and hidden courtyards, pricy renovated apartments and dozens of tiny pocket synagogues. The vibe is a blend of art school hipster and Na Nach hippie, and the vibrant, fantastical images painted on the walls blur the distinction between graffiti and public art.

I brought the fancy camera that Lior’s friend Luciana, an amateur photographer, had given us when she’d bought a new one. If it occurred to me that someone in the neighborhood might not like me using a camera on Shabbat, I dismissed the thought. Sure, there are religious people in Nachlaot, but in my mind they were like the Modern Orthodox Jews I’d grown up with in America, who don’t expect everyone to be Sabbath-observant. There are secular Jews in Nachlaot too, and even, I happened to know, a few Christians. It’s not like, say, Mea Shearim, where shouts of “Shabbes, Shabbes!” would be hurled in my direction, possibly accompanied by a rock or two.

As we wended our way through the narrow lanes, stopping now and then to photograph a clever graffito or a quirky doorknocker, I noticed a man with a sour look on his face about thirty feet behind. I looked back once or twice as we continued on. He appeared to be following us. When we paused in a courtyard for another picture, he approached and confronted me. He seemed nervous but determined.

“What you’re doing is incredibly disrespectful,” he hissed in what sounded like a South African accent. “Walking through an ultra-Orthodox neighborhood with a camera on Shabbat is like burning an American flag in front of US marines.”

My mouth hung open a moment as I fumbled for a comeback, but he abruptly turned and stalked off before I could think of one.

I was hurt and angry, and remained so for much of the afternoon, despite Lior’s effort to soothe my wounded ego. The man’s analogy was inept and offensive, his characterization of the neighborhood inaccurate, and his storming off before I could reply craven.

All the same, thirteen or fourteen years later, I have to admit: He might have had a point.

I often dream of Jerusalem. It’s never the real Jerusalem, but a weird Escheresque collage of multiple hypothetical Jerusalems, with buildings intersecting at odd angles, houses tessellating into temples and back into houses, narrow stone stairways disappearing in all directions into a dense warren of alleyways. Sometimes I’m in a small apartment on an upper story. When I look out the window, it seems the room is hanging suspended over the city, as though at any moment it might fall. I open the door to a bathroom or a closet and find a new, unexpected room that leads me to more rooms and more still, and I understand that this cramped apartment in a modest house is a sprawling mansion defying the limits of physical space. Outside, a stairway leads down to the alley and up into the infinite. The alley below is just like the ones in Nachlaot or the Old City, and leads to another just like it, and another and another, a tangled, enchanting, confounding mess of a maze of a city.

Sometimes I find myself on the outskirts of town, in a menacing slum where smoke drifts up into the sky and no one makes eye contact. Merchants hawk broken wares and people shove and shout. I flee for refuge into the impregnable fortress of the city walls.

I wake up a few minutes before nine on October 7 and immediately reach for my phone, as always. A message from a friend:

Israel attacked. Large scale war.

I am freaking out.

My first instinct is to minimize: What else is new? When is Israel not under attack?

I open WhatsApp, where many unread messages await me in a group chat of Jewish listeners of a certain popular podcast. The first one, sent at 12:26 AM (7:26 Israel time), links to a video of a scene in Ashkelon. Flaming cars spew black smoke skyward as more explosions are heard nearby. It appears to have been filmed from an apartment balcony. #israelunderattack, the caption reads.

I need to call my parents

Alisa is from Ashkelon, an Israeli town roughly the same distance from Gaza City as my home in Silver Spring is from the Washington Monument. Later, she’ll send us a photo her mother took of a hole in their balcony railing made by a piece of falling shrapnel.

Another Israeli, Yael, is visiting her family in Tel Aviv. She responds:

Tell them to stay in because there are videos going around of terrorists driving around

She shares a link to an Instagram post of several videos. The first shows a barrage of rockets. The second, a white pickup stopping in the middle of a road, machine gun-toting men dressed in black piling out of the cab and bed. The third, a man on a paraglider descending from the sky. The fourth, boats coming in from the sea. And on and on.

It looks bad. Like in an unprecedented way.

Israel declared a state of war

Can’t wait to be lectured by American liberals on how to handle this

This last remark, though informed by decades of experience, nevertheless fails to anticipate the depravity of the coming response from a significant part of the left.

A selection of reactions from October 7, hours after the world knew what was happening but before the bodies were cold (or even dead):

what did y’all think decolonization meant? vibes? papers? essays? losers.

–Najma Sharif, contributor to such venerable outlets as Teen Vogue and Bitch Media, as whole families were burned alive or blown to bits in their homes

Decolonization is about dreaming and fighting for a present and future free of occupied Indigenous territories. It’s about a Free Palestine. It’s about liberation and self-determination. It’s about living with dignity. DECOLONIZATION IS NOT A METAPHOR

–Jairo I. Fúnez-Flores, assistant professor of education at Texas Tech, as valiant freedom fighters dreamily fought for dignity by gang raping young women till their pelvises shattered and their vaginas bled

My heart is in my throat. Prayers for Palestinians. Israeli [sic] is a murderous, genocidal settler state and Palestinians have every right to resist through armed struggle, solidarity #FreePalestine

–Yale professor Zareena Grewal, as murderous settler toddlers and genocidal settler old ladies were slaughtered within the internationally-recognized borders of a UN member state3

Shabbat Shalom and may every coloniser fall everywhere

–Barnaby Raine, faculty member of the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research, as his coreligionists’ Shabbat was shattered by the horror he rejoiced in

Nothing will ever be able to take back this moment, this moment of triumph, this moment of resistance, this moment of surprise, this moment of humiliation on behalf of the Zionist entity. Nothing. Ever.

–a giddy, grinning Latifa Abouchakra, employee of Press TV, the Islamic Republic of Iran’s official English-language state media organ, as Israeli hostages ranging in age from baby to Holocaust survivor settled into their Gaza dungeons

October 8:

Every person who died yesterday wasn’t innocent. Every Israeli settler by default is a terrorist.

–speaker at a Philadelphia Hamas rally

Gas the Jews! Gas the Jews!

–mostly peaceful protesters in Sydney expressing legitimate criticism of Israel

October 10:

one group of ppl we have easy access to in the US is all these zionist journalists who spread propaganda & misinformation

they have houses w addresses, kids in school

they can fear their bosses, but they should fear us more 🔪🪓🩸🩸🩸

–UC Davis professor and aspiring serial killer Jemma Decristo, who I do indeed fear more than my boss

October 12:

It is rapidly becoming to [sic] clear that the so-called “final solution” wasn't nearly final enough.

–British author, academic, and, apparently, antisemite Dylan Evans

And on and on:

A woman addressing rallygoers in Vancouver spoke of “the amazing, brilliant offensive waged on October 7.”

A University of Pennsylvania student recalled the “joyful and powerful images which came from the glorious October 7” at another rally. “I remember,” she continued, “feeling so empowered and happy.”

“I love Hamas,” a young man in Harvard Square said after tearing down a “kidnapped” flyer. “I think Hamas should blow the fuck out of Israel. I think they’re all dirty, dirty animals and they all deserve to die. Vermin. They should be all exterminated, every single one of them and their kids, their mothers, their children, everybody just like Hitler did.”

I’ve started dreaming about the Holocaust. Not the one that happened already, but the one that could happen, whether in Europe, the US, Israel, or everywhere. The one I imagine many Jews dream or think or worry about, especially in the diaspora.

Do I think such a thing is likely to happen? Not really.

But do I think it could happen? Of course it could. As my mother likes to point out, the Jews of Weimar Germany thought they were doing great. Many of them considered themselves Germans first and Jews second, if at all. It didn’t matter. Their tolerant, open-minded friends couldn’t save them, and probably didn’t try.

There is little doubt in my mind that many of the morally deranged cheerleaders for terrorism who infest our academic and cultural institutions would gleefully cheer on a mass Jewish casualty event if it were packaged as anti-Zionism in the service of decolonization. They already did it on October 7. Why shouldn’t I believe the same people would react the same way to the same kind of genocidal rampage on a greater scale? If they can not only justify but celebrate and glorify the atrocities of October 7—if they can debase themselves to such an extent, sink to such a depth, if they can suppress and subordinate whatever shred of humanity is left in them to their childishly simplistic black/white, good/evil, powerless/powerful, oppressed/oppressor4 understanding of the world because they read a few pages of Fanon freshman year at Columbia or CUNY or Kalamazoo Clown College and their professor told them that the Jewish state, that tiny splinter of land the size of New Jersey, that pesky thorn in the paw of the Muslim world, is a one-of-a-kind evil, a cancerous colonial tumor that must be excised from the Middle East by any means necessary, and now they’re convinced that almost every Jew with very few exceptions is an enemy of humankind—if they can do all that, it’s not difficult to imagine them doing just a little more. It would hardly be unprecedented in recent human history.

Globalize the intifada!

–popular slogan

We must teach Israel a lesson, and we will do this again and again. The al-Aqsa Flood is just the first time, and there will be a second, a third, a fourth, because we have the determination, the resolve, and the capabilities to fight. Will we have to pay a price? Yes, and we are ready to pay it. We are called a nation of martyrs, and we are proud to sacrifice martyrs. . . . [N]obody should blame us for the things we do. On October 7, October 10, October 1,000,000—everything we do is justified.

–Hamas apparatchik Ghazi Hamad, October 24, 2023

Resistance is justified when people are occupied!

–popular chant

It’s been such an extraordinary day!

–Prof. Grewal again, October 7, commenting on a retweeted video about the massacre

There is only one solution—intifada revolution!

Intifada: The one solution—the only solution—the final solution—to the (((Zionist))) question.

On October 9, I bought a couple Israel T-shirts on Amazon, after trying and failing to find something appropriate among the stacks of musty old clothes in the back of my closet. Among these is a white T-shirt with a picture in blue of Gilad Shalit and the legend “Gilad is still alive” in Hebrew. Gilad Shalit is the Israeli soldier who was captured and held hostage in Gaza for five years before being traded in 2011 for over a thousand Palestinian prisoners. One of these was Yahya Sinwar, currently the top Hamas official in Gaza and one of the architects of the “al-Aqsa Flood” of October 7.

Maybe not the right shirt for the present occasion.

I still have a couple of my old “archaeology worker” shirts too, but random Hebrew lettering wasn’t what I was going for either.

In the end, I settled on two Israeli flag shirts. One reads “ISRAEL” underneath, to eliminate any ambiguity.

Something gnawed at me as I did my shopping. Why am I doing this? Is there a point? Isn’t it just empty virtue-signaling? Well . . . maybe. But that isn’t my primary objective.

Zionism is Nazism!

–slogan written on protest signs by no doubt serious, educated people who definitely know what the word “Zionism” means

It’s not uncommon to see signs at anti-Israel rallies that equate the Israeli flag, or the star of David alone, with the swastika. I want everyone at the university where I work and study to see my shirt and understand that normal everyday people like me won’t be shamed into hiding by hysterical activists screeching facile, historically illiterate nonsense. If some people see my shirt and conclude that I’m a genocidal apartheid-loving white supremacist who eats Palestinian babies, so be it. I’ve received plenty of dirty looks these last few weeks and lived to tell the tale.

A really hot Arab guy just gave me and my Israel shirt a weird look

I should ask if he wants to go somewhere private and solve the conflict together

I’ve gotten some appreciative looks and gestures as well, including from a guy I regularly cross paths with who it turns out is Israeli and greets me in Hebrew now. My muscles tense and my blood pressure jumps as I feel a familiar sense of stage fright, but I manage heroically to gasp out a Boker tov, ma nishma?

I really ought to practice more often.

I took off work on November 14 and went to the rally for Israel in DC. When I arrived on the platform at the College Park Metro station, a crowd of Jewish students wearing kippahs and Israel-themed shirts awaited me. Kippah-less and with my own T-shirt hidden under a jacket, I sat alone on the train, silently expressing solidarity now and then with a smile or a look that most likely went unnoticed.

I met up on the Mall with some friends from the group chat. Most were Jewish, but a few token goyim had come to show support. Alisa, a Belarusian-Israeli-American who lives in DC, was the only one I’d met before, but I felt a sense of communion with these internet weirdos I’d met through a podcast’s comments section. ChayaLeah, another attendee, had flown in from California for the rally. She’s a member of Chabad, a tightknit Hasidic community known for its outreach to less observant Jews. Many of her fellow Chabadniks—all of whom she seemed to know and/or be related to—were in the crowd. Among them were pairs of teenage boys asking bare-headed men if they wanted to put on tefillin. Eventually, inevitably, they zeroed in on me.

“Ehhh, I dunno . . .” I said. “I don’t think I’ve put tefillin on since high school.”

(And . . . ? Is that a reason not to do it now?)

I politely declined.

But the tefillin patrol caught up with me again about an hour later. They approached and engaged me before I could make any evasive maneuvers.

“Do you want to put on tefillin?”

“Um . . . Yeah, okay, fine.”

One of them produced the arm piece while the other waited. I slipped my arm through and positioned the box over my bicep.

“Baruch,” the kid prompted with the first word of the blessing.

“You can give me more than a word at a time,” I said, reflexively defensive. “I just . . . don’t remember the exact wording.”

I repeated the blessing after him.

“Okay, seven times around the arm, right? Sorry about my giant head,” I added, as he pulled the head piece over my skull. I wasn’t sure what came next. I figured I wasn’t going to go through an entire prayer service.

“Shema—” he started.

“Shema Yisrael Adonai Elohaynu Adonai echad.”

Hear, o Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is one.

“Baruch—”

“Baruch shem kevod malchuto le’olam va’ed.”

Blessed be the name of the glory of His kingdom forever and ever.

“That’s it. You can take a moment for yourself.”

I lowered my eyes and stared in silence at the grass, concentrating on feeling something. I thought of the Western Wall and of the people praying there and of myself praying there. I thought of the Hasidic shul in Mea Shearim where Hillel and I had gone on a whim one Friday night, where the children stared at me like I was from another planet because I’d worn a blue shirt but I was moved by how the men prayed, arms half-raised with the palms up, faces upturned and shouting out the words, shouting up to the heavens as though anxious God might not hear. I thought of prayers I hadn’t said, customs and commandments I hadn’t followed, books I hadn’t read, people I hadn’t met. I thought of communities I’d belonged to but didn’t anymore. I thought of the thousands of people gathered now on the Mall and the millions, interconnected, encircling the globe. I thought of this new group of friends I’d recently made, and of others I might still meet.

“Okay,” I said, looking up. As I began to unwrap the leather arm strap, I thought of my own tefillin waiting in a drawer at home.

An inexpensive housing facility for new immigrants.

Hebrew school.

Fact check: Palestinians do not, in fact, have a right to rape, mutilate, torture, murder, dismember, and kidnap civilians.

“There is no question who the oppressors are who the oppressed are,” Yale’s Prof. Grewal tweeted on October 10. “And somehow people are confused about this. White supremacy never stops being shocking to me.” In a tweet on October 7, Grewal responded to a journalist’s suggestion that civilians shouldn’t be massacred with crystalline moral clarity: “Settlers are not civilians. This is not hard.” Indeed, it’s frightening how easy it is for simple-minded people to dehumanize others and themselves with simple-minded binary thinking.

Wonderfully written, Benjy! Thank you so much for publishing this.

Just wonderful. Makes me want to make my dream of retiring to Tel Aviv as a goy bartender come true even harder.