Hilaire Belloc and the Jews

The first in a three part series on how the mostly forgotten writer's "admirable Yid book" is and isn't still relevant today

As I mentioned in an earlier post, I was working on a series of essays about biblioantisemitism (which is a totally real word I didn’t just make up). Well, that was in July, and I’m still not done. I worked and I worked till I had over 4,000 words on my hands and enough thoughts and ideas for another couple thousand. The dual task of finishing the piece and cutting it down to something anyone would want to read was just too daunting, and I let it fall by the wayside.

Well, I’ve decided to return to the project, but instead of a single very long essay (let’s face it, I can’t bring myself to cut anything), I’m dividing it into three parts. This is the first. The second is done, and I’ll publish it pretty soon. The third is still under construction, but I hope to have it done before another four and half months have passed.

One last thing before we get to the main event: I want to know whether essays of this kind are of interest to anyone but myself. So if you like this post, please click the “like” button (that’s the circled heart icon), share it with anyone you think might be interested, and if you haven’t already, subscribe. If you don’t like it or you have any other feedback, feel free to leave a comment telling me why I’m terrible.

The more views and subscribers I get, the more motivated I’ll be to try to post more frequently. I have no illusions of becoming a Substack millionaire anytime soon, but . . . maybe someday? Help me bring that day a little closer.

Okay, so: Antisemitism.

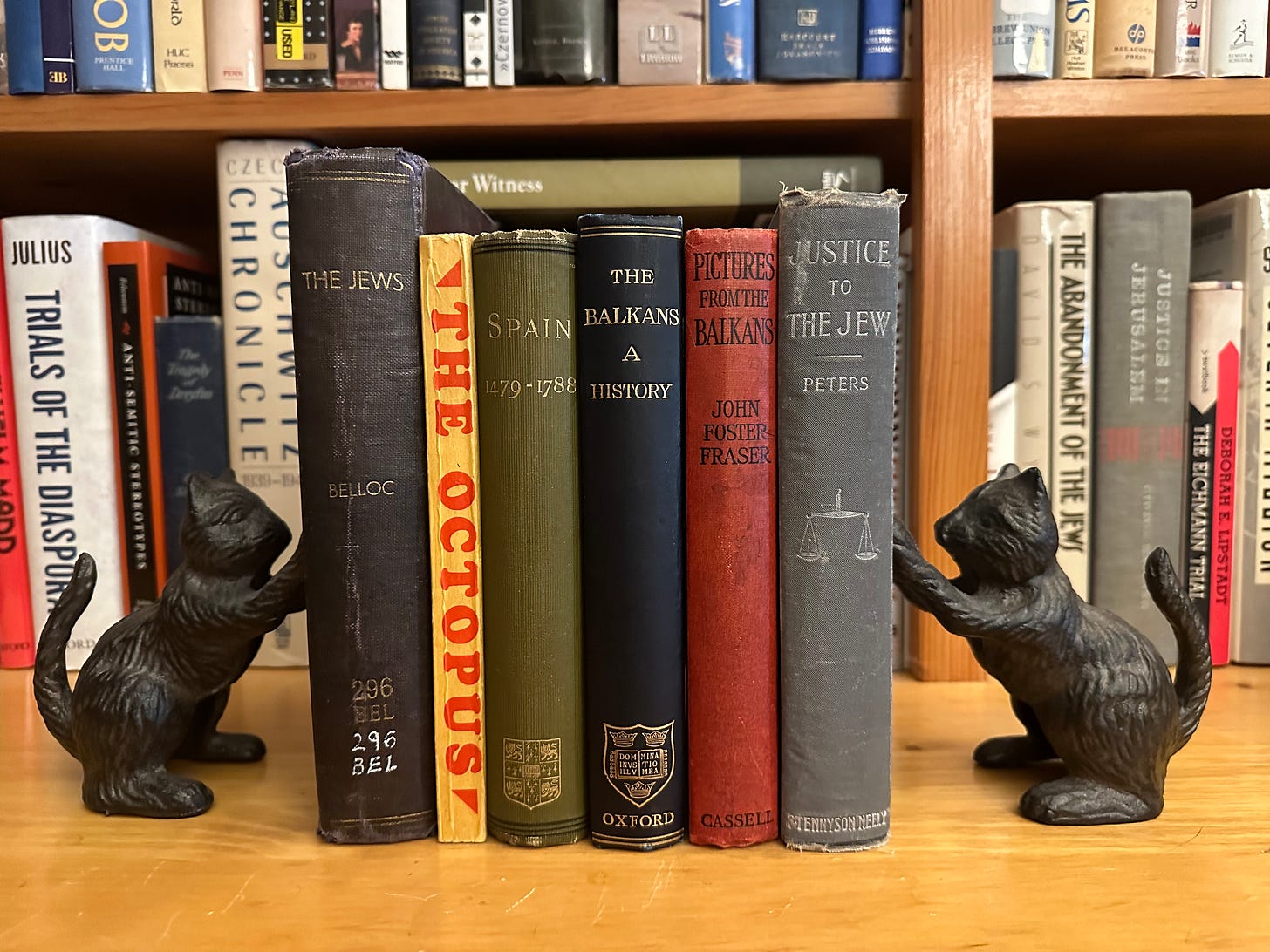

I have no shortage of books about antisemitism, and many others that contain it—Oliver Twist is an obvious example, as are dozens or hundreds of other works of literature. But the crown jewels of my Judeophobia collection are the two that simply are antisemitism from cover to cover: The Jews (1922), by the English writer Hilaire Belloc; and The Octopus (1940), by a certain Rev. Frank Woodruff Johnson, which I’ll talk about in a future post.

Hilaire Belloc (1870-1953) was an English Catholic of French origin, perhaps best known today as a close friend of the better-known antisemitic English Catholic writer G. K. Chesterton. His children’s poem “Matilda, Who told Lies, and was Burned to Death” provided fellow English antisemite Roald Dahl with the title for his book Matilda. He published dozens of books in various genres, from fiction and poetry to history and travel writing to a multivolume1 poison pen assault on H. G. Wells’ Outline of History, which he deplored for promulgating “the old and exploded theory of Darwinian natural selection,” among other similar crimes against Catholic feeling.

But evolution was a mere foot soldier among the motley forces Belloc saw arrayed against his embattled vision of Christendom. In a letter to Robert Speaight, who published an early Belloc biography in 1957, he had this to say about a far more powerful division in that army:

The poor darlings, I’m awfully fond of them and I’m awfully sorry for them, but it’s their own silly fault—they ought to have let God alone.

Can you guess who he’s referring to? Hint: It ain’t the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Even for his time, Belloc’s attitudes toward Jews were a bit much, both in substance and in the amount of time and energy he devoted to them. Though not as hateful as the most virulent antisemites, Belloc had, in Speaight’s words, “a chronic preoccupation” with the Jews.

The origin of this preoccupation is obscure. It was not instilled in him from a young age; his French father died when he was two, and his liberal English mother was, if anything, a tad philosemitic.2 His prejudice appears rather to have been a decision he made as an adult. “It was the Dreyfus case that opened my eyes to the Jew question,” he said later in life, referring to the 1894 conviction of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army, on trumped up charges of treason. Many at the time, notably Emile Zola, thought Dreyfus had been railroaded. But for those driven less by reason than resentment, Dreyfus was a handy scapegoat, a living embodiment of centuries of anti-Jewish mythology.

Why did Belloc get caught up in the anti-Dreyfusard fervor, rather than joining forces with Zola in opposing the corruption and antisemitism of the French military? In a 1984 biography, A. N. Wilson suggests that the Dreyfus Affair didn’t open Belloc’s eyes to the “Jew question” at all. Rather, “it was his year in the French army which closed his mind to the ‘Jew question’ before the Dreyfus Affair had ever happened.” Belloc didn’t speak French like a native, and his name sounded suspiciously Jewish to his fellow soldiers. He became an antisemite, Wilson suggests, in order to fit in—all the cool kids were doing it.

(Belloc’s brothers in arms might have been on to something with regard to his name: “His French ancestry,” Wilson writes, “stemmed from a seventeenth-century Nantes wine-merchant whose name was Moses Belloc or Bloch, scarcely the most gentile of names.” In later years he’d laugh this off and “dismiss” any suggestion of Jewish blood “with raucous contempt.” But as a young recruit in the French army two years before the Dreyfus Affair, playing it cool and confident might not have been his preferred approach.)

This explanation doesn’t account for the specifically Catholic aspect of his antisemitism, but it seems plausible that the company he kept at this formative time contributed to the development of his beliefs. In any event, says Wilson, the Jews were a perennial “obsession” for Belloc for the rest of his life.

In Trials of the Diaspora, his magisterial survey of English antisemitism, Anthony Julius runs down Belloc’s lengthy rap sheet of antisemitic statements and writings. These include a cartoonishly nefarious and shadowy Jewish villain in his novel Emmanuel Burden; his furious efforts to whip the Marconi scandal—a case of insider trading that happened to involve, among others, a few Jews—into a new Dreyfus Affair; and his pioneering template for Holocaust denial that David Irving and his ilk would perfect decades later.3

But The Jews was his crowning achievement. It gathered all his antisemitic beliefs and systematized them in a single compendium of prejudices, grievances, and conspiracy theories. It was, in Julius’ words, “a more discursive, more reflective, assault on the Jews.”

Despite all this, Belloc protested his innocence in a 1924 letter:

There is not in the whole mass of my written books and articles, there is not in any one of my lectures (many of which have been delivered to Jewish bodies by special request because of the interest I have taken) there is not, I say, in any one of the great mass of writings and statements extending now over twenty years, a single line in which a Jew has been attacked as a Jew or in which the vast majority of their race, suffering and poor, has received, I will not say an insult from my pen or my tongue, but anything which could be construed even as dislike.

Keep that in mind as we explore the manifesto he once referred to as his “admirable Yid book.”

Belloc takes pains throughout his 308-page investigation of the “Jewish Problem” to insist that he’s not an antisemite. He doesn’t hate Jews—Heavens no—he just thinks they can’t inhabit gentile society without being hated by others, that they are as much to blame for this as the gentiles who hate them, and that something simply must be done. In fifteen lucid and neatly-ordered chapters, he describes the problem thoroughly and systematically, and offers his humble suggestions towards a solution that will be mutually beneficial for both Jews and their long-suffering “hosts.”

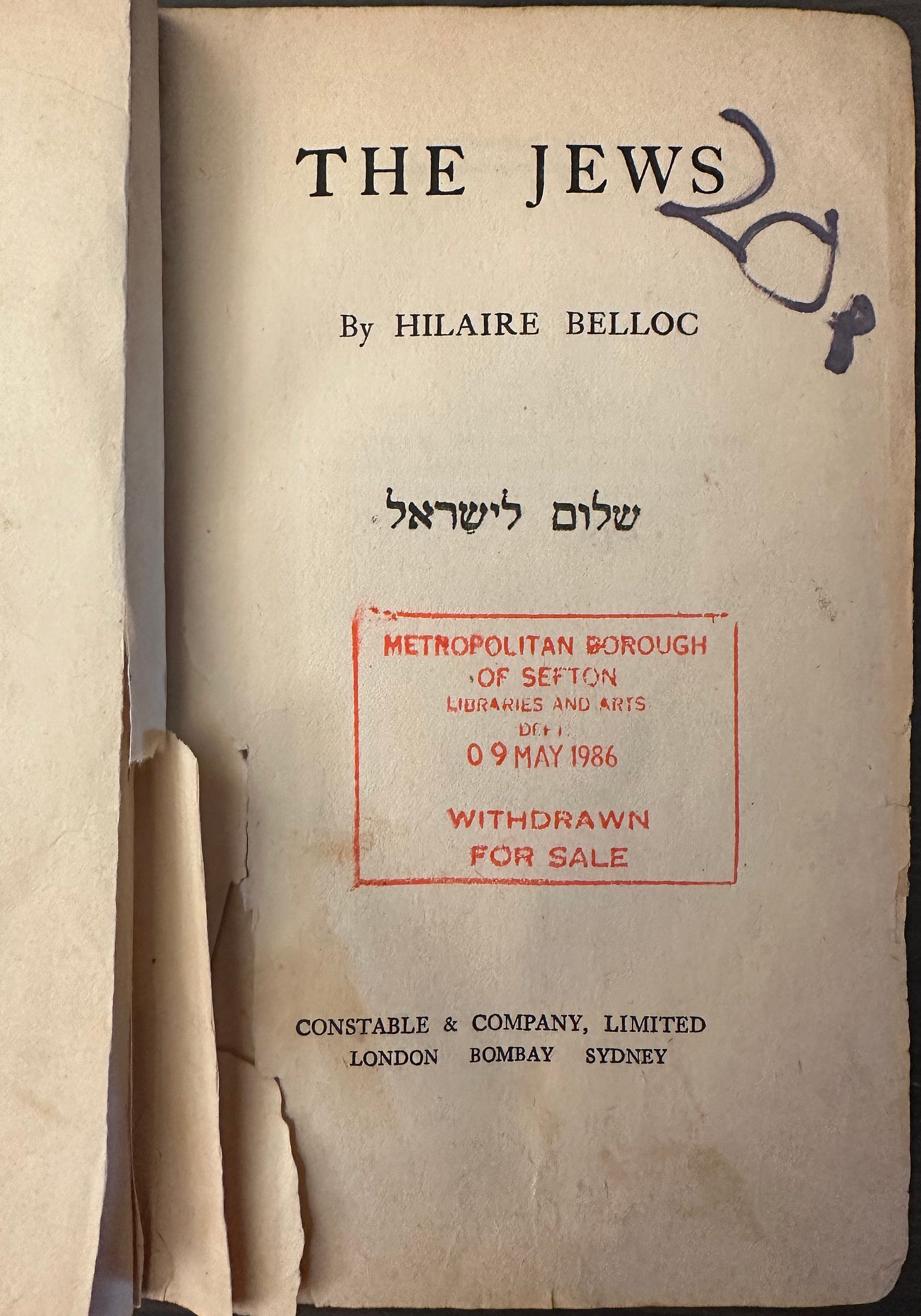

His abundant warm feelings first appear on the title page, which is graced by the Hebrew words shalom le’Yisrael, or “peace to Israel.”

The dedication page features a charming encomium to his Jewish secretary:

Isn’t that sweet?

How then, you ask, can this book be antisemitic? Is it my “instinctive policy . . . not only to use ridicule against Anti-Semitism but to label as ‘Anti-Semitic’ any discussion of the Jewish problem at all, or, for that matter, any information even on the Jewish problem”?

If, like Mr. Belloc, you find yourself asking that question, you may agree with some of his other key points, chief among which are

that the continued presence of the Jewish nation intermixed with other nations alien to it presents a permanent problem of the gravest character: that the wholly different culture, tradition, race and religion of Europe make Europe a permanent antagonist to Israel, and that the recent and rapid intensification of that antagonism gives to the discovery of a solution immediate and highly practical importance.

This jibes with a slogan of Belloc’s well-known to both fans and detractors: “The Faith is Europe and Europe is the Faith,” which seems to imply that those not of the Faith cannot be European. Honestly, it was generous of him to count Protestants as Europeans, considering “the Faith” he so reveres is Roman Catholicism. But the Jews? Well! That’s a different story:

You cannot have your cake and eat it too, you cannot at the same time have present in the world this ubiquitous fluid, yet closely organized Jewish community, and at the same time each of the individuals composing it treated as though they were not members of the nation which makes them all they are. You cannot at the same time treat a whole as one thing and its component parts as another. If you do, you are building on contradiction and you will, like everybody who builds on contradiction, run up against disaster.

Though Belloc distances himself from irrational antisemites driven by fear and hate, he insists that “[t]he Anti-Semitic movement is essentially a reaction against the abnormal growth in Jewish power, and the new strength of Anti-Semitism is largely due to the Jews themselves.” Previous generations, he claims, were more open and accepting, because they pretended to believe that it was possible for a Jew to be an Englishman. But now? Between the outsized power, the money, industrial capitalism (but also “Jewish Bolshevism”), clannishness, secrecy—British patience is wearing thin.

His solution is a kind of mutually agreed-upon apartheid. He’s very sketchy on the details, devoting only a few pages to vague concepts of a plan, as he fears specific ideas will soon become impracticable as antisemitism boils over. What it comes down to is “recognition and respect.” Both the Jews and their English “hosts” should drop all pretense and acknowledge Jews as a separate nation and an alien race, their foreign blood immiscible with that of true-born Englishmen. This separate nation status is to be regarded as a “privilege.” At the same time, gentiles should socialize with Jews to better understand and respect them, maybe even befriend them—but nothing more. No more intermarriage. No more joint business ventures. Certainly no more Jews in government and finance, where too many men named Rothschild have been allowed to pull all the strings.

Belloc does not, to begin with, wish to enshrine these precepts in law. Imposing laws on the Jews without first fostering a culture of separation will breed resentment and resistance. Instead, he encourages Jews and gentiles alike to be open about their distinct nationalities, and writes approvingly of existing Jewish institutions that run parallel to English ones. His goal is to reverse whatever assimilation has taken place. The more the Jews are assimilated, the greater the shock of the inevitable backlash.

What’s more, Jews’ futile attempts to assimilate have only created further enmity. Belloc is particularly incensed by Jews who trade in their Jewish-sounding names for generic English (or German, or French, etc.) ones. Though he acknowledges the reasons they may once have had for doing so, he insists that such measures surely aren’t needed in the modern, woke England of 1922.4 No, Belloc wants his Jews out, proud, and unambiguously denominated.

This nomenclatural concern was echoed by his friend Chesterton in The New Jerusalem (1920), a travelogue of his journey to the Holy Land, but the point is overshadowed by a far more whimsical idea. Chesterton proposes, perhaps not quite in earnest but not entirely in jest, that Jews be allowed to participate in English society and government at any level, from Chief Justice to Archbishop of Canterbury, on the sole condition “that every Jew must be dressed like an Arab.” This policy will, he insists, lead to “healthier relations with [the Jew]. The point is that we should know where we are; and he would know where he is, which is in a foreign land.”

This is the condition Belloc and Chesterton set for the Jews: You may reside within our borders, but you must never forget that you do not belong here, that your presence is a burden to us, and that we do you a superhuman kindness by tolerating you at all.

In part two, we’ll take a look at Belloc’s views on an obvious alternative to this state of affairs: Zionism.

More specifically, a book and a pamphlet. In response to a recently-published revised edition of Wells’ 1920 doorstop, Belloc published A Companion to Mr. Wells’s “Outline of History” in 1926. Wells responded the same year with Mr. Belloc Objects to "The Outline of History". Not to be outdone, Belloc shot back with Mr. Belloc Still Objects to "The Outline of History" in 1928. Wells, I like to imagine, sighed and rolled his eyes.

She was friends with George Eliot, who had had her own journey from antisemitism to philosemitism, culminating in the publication of her Daniel Deronda, one of the only Victorian novels to feature a sympathetic Jewish character.

In 1938 he wrote skeptically in the press of a particularly brutal Nazi atrocity that had recently been reported. How can we be sure this really happened, and if it didn’t, why should we trust anything the Nazis’ opponents say? He demanded proof. When, after a few weeks, no one had responded to him, he pointed to this silence as reason to doubt any such accounts in the future.

If you’re having trouble squaring this assertion with his concern about rising antisemitism, I’m right there with you.

Looking forward to Part 2! Thank you for this!

How very strange! But were those not strange times; experiments in the democratizarion of some European countries along with many Jews rushing to assimilate as they could at last be considered citizens. And so Belloc’s reaction to those “disturbing” developments, trying to appear sophisticated and humane at the same time as reacting instinctively, driven by deep prejudice.

(Seems appropriate to see “The Abandonment of the Jews” on your bookshelf. The follow up… ?)